How is your business fostering a culture of inclusion and support for workers with disabilities?

These disabilities may range from visible or non-visible physical ailments to mental health conditions to intellectual differences. We know that the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination and ensures equal opportunities for individuals with physical or mental impairments. But how can organizations move beyond compliance to fully realize the benefits of accommodating diverse workforce needs?

Almost 19 million people with disabilities contribute to today’s workforce, and Forbes reports that these employees bring advantages such as higher revenue and enhanced productivity to their organizations. In fact, one report showed that companies leading on key disability inclusion criteria generate 1.6 times more revenue, 2.6 times more net income, and twice the profit margins of companies that are less supportive.

A commitment to inclusion leverages the value of all employees to reap synergies and maximize outcomes in the workplace.

In this panel Q&A, four experts from Fit For Work share real-world insights, challenges, and creative solutions for supporting workers with disabilities in industrial settings. From adaptive tools to inclusive scheduling, their experiences highlight how thoughtful accommodations can unlock productivity, innovation, and belonging on every shift.

Meet our panel:

- Wendy Chelette, OTR – Director of Employment Testing

- Rupert Edwards, BS, AHFP – Ergonomic Specialist, Testing Technician

- Ashley Mayo, PT, DPT, AEP – Injury Prevention Specialist

- Forrest Richardson CSP, ARME, CSM – Director of Safety

What does “inclusion on every shift” mean to you?

Forrest: In the context of the ADA and reasonable accommodations, inclusion means that employees with disabilities have equitable access to work opportunities and responsibilities. It means inclusion in team dynamics and an equal opportunity to work any shift (with no “shift segregation”), accompanied by consistent support and accommodation, such as assistive devices, modified work tasks, or communication support.

Rupert: Inclusion on every shift means ensuring all team members feel respected, heard, and able to contribute. In an industrial setting, it includes clear communication, equal access to personal protective gear (PPE) and safety knowledge, and encouraging input. People with visible or invisible disabilities receive support, enabling everyone to work safely and confidently.

Inclusion means acknowledging the differences among people and actively working to create spaces that consider the various abilities of all. – Ashley Mayo

What are some common ADA compliance challenges in facilities, and how can employers address them?

Forrest: Managers struggle to determine whether a requested accommodation is “reasonable” or would cause “undue hardship” in terms of cost, disruption, or operational burden. Accommodation is especially complex in small or understaffed operations, safety-sensitive positions, and shift work environments. Human Resources (HR) can help by coordinating an interactive process with the employee to clarify job functions, disability-related needs, and accommodation options.

They can analyze costs, productivity impacts, and staffing implications while documenting all steps and justifications to ensure ADA compliance and legal defensibility. Environmental Health & Safety (EHS) can evaluate the safety implications of proposed accommodations. They may also recommend engineering or administrative controls to support safe inclusion.

Wendy: Workers with disabilities sometimes surprise us with new techniques or innovations for performing essential job functions. Those with lifelong physical disabilities learn to live with these limitations and often develop creative ways to complete a task. This creativity can benefit employers, bringing innovation, experience, and diverse perspectives to performing essential tasks. Sometimes, employers discover that employees with disabilities are their most effective workers.

A common challenge is striking a balance between reasonable accommodation and workplace safety. While employers are required to consider accommodations, they are not required to implement changes that pose a direct threat to the health or safety of the individual or others. It may be necessary to explore alternative roles or accommodations. – Rupert Edwards

What is one example of accommodation that has worked well in a hands-on or industrial role?

Wendy: An order selector candidate at a large frozen distribution warehouse presented with a congenital claw-hand deformity of the dominant hand. They demonstrated the ability to meet all functional testing criteria for the position. However, since the position was within a frozen warehouse, heavy PPE gloves were required, with modifications needed. Even then, it was unknown how well the candidate would be able to grasp weighted product repetitively.

A reasonable accommodation request was made to place them in a warehouse environment that did not require gloves, such as a dry goods warehouse with ambient temperatures. The employer approved this request and successfully hired the candidate.

Forrest: A client inquired whether a forklift operator candidate with only one foot was legally permitted to operate a powered industrial truck under ADA rules. The answer is “yes,” according to ADA and OSHA interpretations; this is a reasonable accommodation if they can operate the truck safely and pass OSHA-required training and evaluation.

The key is to assess ability, not disability, and to explore whether accommodation can enable safe operation without a direct threat to health or safety.

Employers should design tasks and accommodations that don’t require individuals to disclose a disability first. This approach makes accessibility embedded, not conditional. – Ashley Mayo

What tools, equipment, or workstation modifications have you used/seen to support workers with physical limitations?

Rupert: While automated tools can be highly effective, often, the layout or method of operation makes a difference.

For example, replacing a hand-operated control with a foot pedal can significantly enhance accessibility, enabling individuals with limited hand dexterity to use the equipment safely and effectively.

Simple design changes can open the door for a broader range of workers to participate fully in industrial roles. This could also improve the body mechanics of all employees.

Forrest: I recommend task rotation based on functional strengths, not just ergonomics. An employer can restructure workflow to align specific tasks with an employee’s physical capabilities, while still maintaining fairness in work distribution.

For example, an employee with limited mobility in one leg is rotated into inspection, monitoring, machine-watching, or quality control roles with seated work options. This approach minimizes strain without removing the employee from productive, visible roles. It also promotes inclusion and meets ADA requirements.

Creative solutions can make a difference for sites with limited equipment or resources. A client has only a few scissor lift tables but many tasks that require low-level lifting. One of their workers uses a forklift to elevate pallets, allowing them to work and lift from waist level. – Ashley Mayo

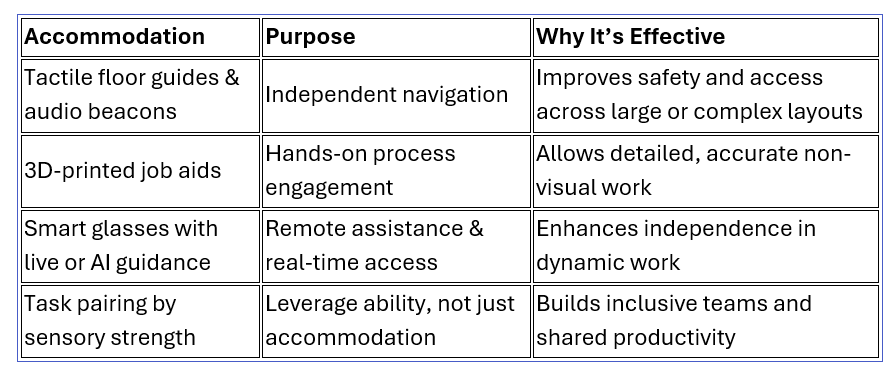

What accommodations have you implemented/seen for workers with low vision or blindness?

Forrest: The following are some unconventional but effective accommodations for workers with visual impairments, beyond the more common tools such as screen readers or white canes. These examples demonstrate how creativity and inclusion can go hand-in-hand with ADA compliance:

Ashley: Common color blindness (especially red-green) should be acknowledged when designing signage, avoiding visuals that rely solely on color detection.

An inclusive stop/go button includes shapes, texts, and icons. The Purkinje shift, which occurs in low-light settings, explains that people are more sensitive to blue-green light and less sensitive to red light; therefore, alerts or signs with red colors or lights may not be visible. Military and aviation environments frequently utilize blue-green lighting to enhance night vision.

High color contrast helps convey messages through signage (e.g., avoid using yellow text on a white background). Finally, the ability to perceive color decreases with age, so include visual cues along with color to support an aging workforce.

Most people instinctively want to assist someone with a disability, even grabbing their arm without asking. Many people make assumptions about what tasks they can or cannot do or speak about them rather than to them. In reality, many blind or visually impaired employees have highly developed systems for navigation and task execution. They thrive on independence and equity, not sympathy. – Forrest Richardson

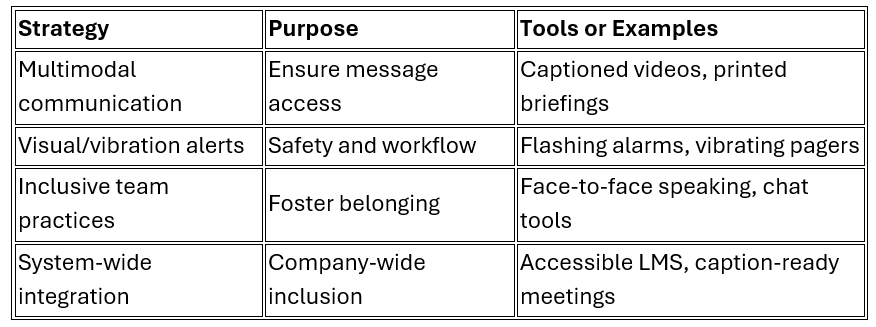

What accommodations have you made/seen for workers who are deaf or hard of hearing, especially in high-noise environments?

Rupert: Thoughtful accommodations can remove barriers and promote inclusion. A major grocery retail testing department had a high-noise setting with flashing lights, making communication challenging for individuals with hearing loss.

During a multi-week training program, the company hired a sign language interpreter to support deaf participants alongside hearing peers. The interpreter stayed with the group, translating instructions and discussions in real time to ensure that everyone received the same information, remained fully engaged, and felt included.

Forrest: To better integrate communication tools and practices for hearing-impaired team members under the ADA, employers must ensure equal access to information, safety communication, and team interaction across all levels of the organization. Here is a plan to do that effectively:

Integrating visual communication tools is essential for hearing-impaired team members. Post clear, easy-to-follow information and check in periodically to confirm understanding and invite questions. Provide written versions of protocols and procedures to reinforce key information and ensure that all team members stay informed. – Rupert Edwards

How can employers support workers with non-visible disabilities or differing abilities, such as mental health conditions or neurodivergence, in industrial roles?

Rupert: Support for mental health or neurodiversity begins with creating an inclusive and stigma-free environment, providing clear communication about available accommodations, offering flexible scheduling whenever possible, and training supervisors to recognize and respond empathetically to signs of distress.

Implementing job modifications and utilizing assistive technologies tailored to individual needs, while maintaining safety protocols, is essential. Encouraging open dialogue and fostering peer support helps workers feel valued and supported, benefiting both the individual and the team.

Wendy: Recently, we had a testing candidate who presented with dyslexia and requested accommodation for assistance reading warehouse signs and product labels. His job coach recommended a reading pen that could scan product labels and read the content aloud to him.

The employer was open to this accommodation and provided a pen. Being open to simple accommodations enables employers to place skilled workers in roles where they can thrive.

Take a people-first approach to understand challenges, goals, and needs. Ask questions such as, “Would a checklist be useful?” or “Should we break this task into steps?” Open the door for support without forcing someone to disclose a diagnosis. Include them in the process and then test your solutions for validation. – Ashley Mayo

What lessons have you learned about balancing compliance with compassion to support disabled workers?

Rupert: While everyone deserves the opportunity to work, we must ensure that individuals aren’t placed in roles that could put their safety or the safety of others at risk. A person may want a particular job due to financial reasons, but that role might not be the best fit for their condition. Ultimately, prioritizing safety must come first because, without safety, no job opportunity truly benefits anyone.

Ashley: Compliance sets the floor, not the ceiling. It’s essential to follow the standards while understanding the “why” behind them. When we lead with empathy and listen to workers’ actual challenges, we can develop solutions that go above and beyond the minimum requirements and support everyone better.

“Reasonable” doesn’t mean “minimal” but rather workable for all. A reasonable accommodation should support the employee in performing essential job functions effectively and with dignity, not just meet the bare legal threshold. Compassion involves seeing the employee as a whole person. – Forrest Richardson

Conclusion

What additional steps can your organization take to foster a culture of inclusion and support for workers with disabilities?

When addressing disabilities ranging from visible or non-visible physical ailments to mental health conditions to intellectual differences, there are many opportunities for accommodation. Organizations can shift from simply meeting legal requirements to actively embracing the benefits of supporting all employees.

Creating a truly inclusive workplace isn’t just about compliance—it’s about designing environments where everyone has the opportunity to thrive.

At Fit For Work, we believe that safety and inclusion go hand in hand. We help businesses create safer, more accessible workplaces through strategic planning, targeted training, and proven risk mitigation. If you’re ready to strengthen your safety program while supporting the needs of every employee—including those with disabilities—contact us today.

Resources

• Job Accommodation Network (JAN) – askjan.org

• U.S. Department of Labor – Office of Disability Employment Policy (ODEP) – dol.gov/agencies/odep

• National Organization on Disability (NOD) – nod.org

• Institute for Human Centered Design (IHCD) – humancentereddesign.org

• AbleData Archive (now hosted by NIDILRR) & Assistive Technology Industry Association (ATIA) – atia.org

• ADA National Network – adata.org

Our Experts

Wendy Chelette, OTR – Director of Employment Testing, Fit For Work

Click here to read more from Wendy.

Rupert Edwards, BS, AHFP – Ergonomic Specialist, Testing Technician, Fit For Work

Click here to read more from Rupert.

Ashley Mayo, PT, DPT, AEP – Injury Prevention Specialist, Fit For Work

Watch Ashley share expert ergonomic strategies in “Ergonomics Evolved: AI, Insights, and the Future of Workforce Performance” — available on-demand.